Experience the Past, Enjoy the Present

Let us tell you about the man and his family who lived here.

He was a poet, a painter, a shoemaker, an entrepreneur. He was a leader of his church, a music composer, a Kansas sheep farmer, a cotton farmer in southeast Missouri and a miner in southwest Missouri. He was a prison reformer, the owner of a telephone company, a world traveler.

And he lived in this house at 624 E. Capitol Avenue in Jefferson City, Missouri.

He loved to tell people that his boyhood home was the first house consumed by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 when wind swept the flames from the barn of Patrick and Catherine O'Leary at 137 DeKoven Street to his family home. The barn and the Parker family home (if the story is true) were the first of 17,500 structures destroyed in the fire.

(A brief departure if we might: "Big Jim O'Leary, who was two years old when the fire started and grew up to become a "notorious saloon proprietor and gambling kingpin," often complained that the "musty old fake about the cow kicking over the lamp gets me hot under the collar" and asserted that the fire was caused by spontaneous combustion of newly-harvested hay put in the barn a day earlier. Critics dismiss that story, as well as the cow story, because the summer of 1871 had been "one long and merciless heat wave" that would have thoroughly dried the hay before it was put in the barn, making spontaneous combustion unlikely).

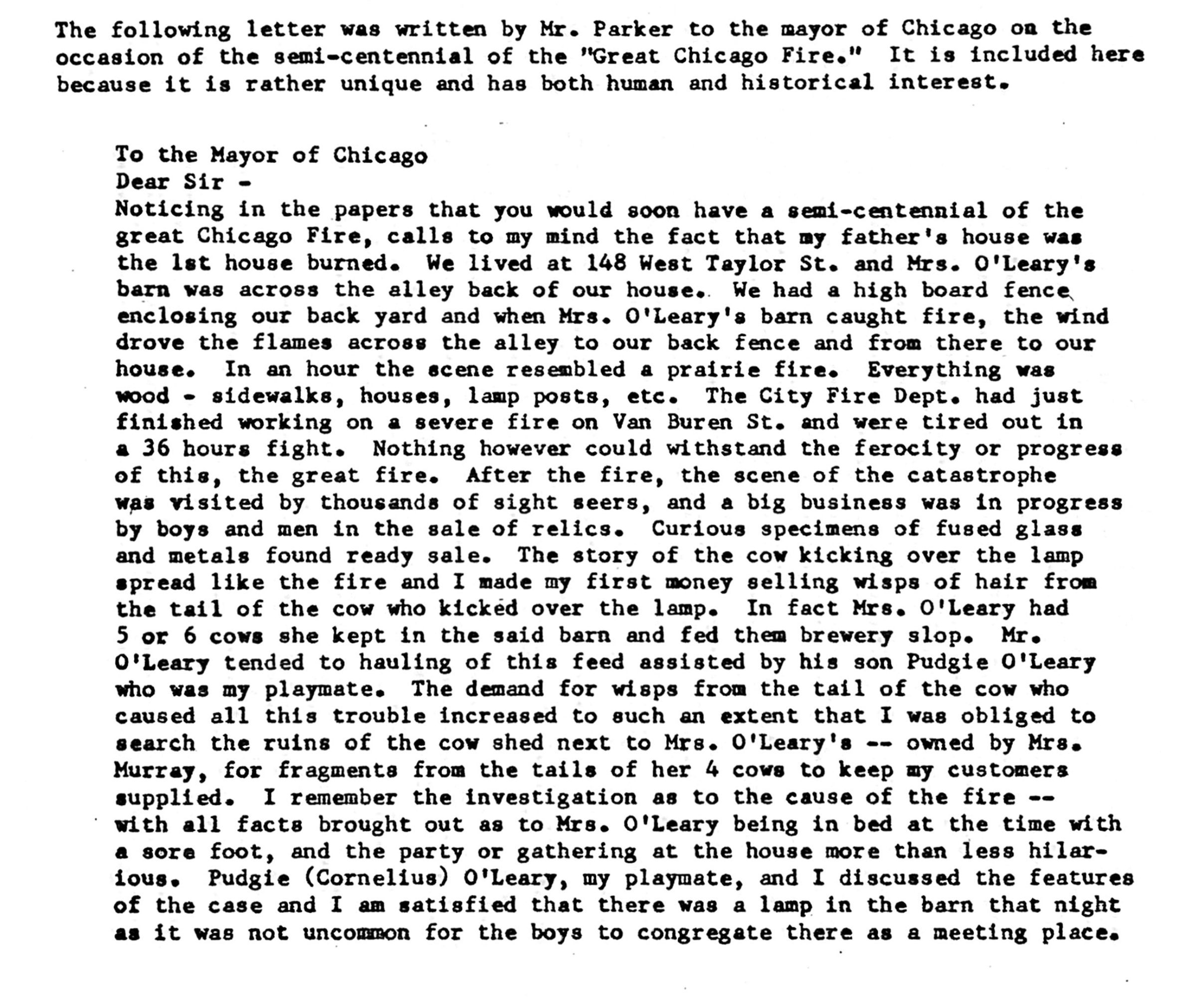

In 1921, as Chicago was preparing to celebrate the centennial of the fire, Parker sent a letter to Mayor "Big Bill" Thompson offering a first-hand account of the fire. He said his home at 148 West Taylor Street was separated from the O'Leary barn by an alley and a tall fence. The story of the cow kicking over the lantern gained strength in the immediate aftermath.

And young Lester Shepard Parker, one day past his eleventh birthday, saw a way to make a profit from the rumor. As visitors combed the ashes for relics to take home as souvenirs, Lester found a way to make his first money. He wrote in his 1921 letter:

"In fact, Mrs. O'Leary had five or six cows which she kept in the small barn and fed them brewery slop…The demand for wisps of the tail of the cow which caused all this trouble increased to such an extent that I was obliged to search the ruins of the cow shed next to Mr. O'Leary's, owned by Mrs. Murray, for fragments from the tails of her four cows to keep my customers supplied."

He maintained the real cause of the fire was Mr. O'Leary's fondness for "red liker" and Mrs. O'Leary's refusal to let him drink in the house. Mr. O'Leary decided to "confine his drinking partys [sic] to the barn."

"Pudge O'Leary (a playmate of young Lester's) and I discussed all the features of the case and I am satisfied that there was a lamp in the barn that night as it was uncommon for the boys to congregate there as a meeting place." Parker suggested the drinking party, denied access to the house, took their gathering to the barn where one thing led to another, the Chicago Fire in this case.

Parker was born October 7, 1860 in Worcester (they pronounce it "Wooster" there), Massachusetts. His father, George, worked for Phelps, Dodge & Palmer, a boot and shoe manufacturing company. The job took the family to Lexington, Kentucky when Lester was three and then five years later to Chicago. Lester seems to have had a natural penchant for shoe-making. He handmade one when he was nine years old.

When the family retreated to Worcester after the fire, Lester became active in the Massachusetts Natural History Association's ornithology efforts. Lester attended the Worcester Academy as a teenager and graduated in 1879 "with a background in Law" from Baltimore City College (at the time a combination of prep school and junior college), in Maryland.

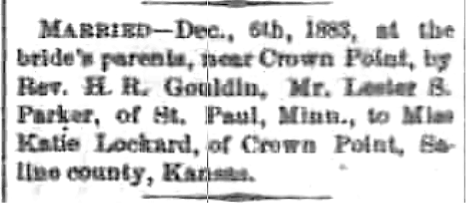

He was 19 when he moved west to Salina, Kansas where he prospered as a lawyer and as a rancher raising sheep and cattle. It is not clear why he abandoned Salina and moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, to be the foreman of the Kellogg and Johnson shoe manufacturing company. But during that time in Kansas he met Katie Lockard and returned to marry her.

Salina, Kansas Saline County Journal, December 13, 1883 page 3

They had a daughter, Gracie, and two sons, Clyde and Dan.

He spent a brief time in Chicago helping the C. M. Henderson & Company organize the Jefferson Shoe Company that began producing shoes within the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City. Although The Illustrated Sketch Book and Directory of Jefferson City and Cole County, 1900 says Parker moved to Jefferson City in 1895, he and Katie obviously were here much earlier, perhaps as early as 1887. A family birth record shows that their first child, Grace, was born in St. Paul in 1884. Their second child, Clyde, is shown as having been born in Jefferson City in July, 1887 and their third son, Daniel, is shown as being born in 1889, also in Jefferson City.

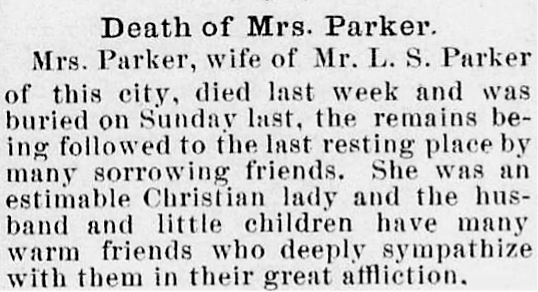

Cole County Democrat December 4, 1890. Page 3

Clyde West Parker (his middle name was his grandmother's maiden name) died at the age of three. When Katie died November 28, 1890, she was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Jefferson City next to Clyde. Grace Ellen Parker (Williams) died in 1955. Daniel Lee Parker died in St. Louis in 1935.

The earliest mention discovered in the local press of Lester Parker is in the Jefferson City State Republican of May 19, 1892, a short note in the "Personal" column on page three that Lester had left for a business trip to Boston.

He had achieved some notoriety as a singer, however. He was part of a quartet that performed three songs at the high school commencement exercises in May, 1893: Come Rise With the Lark, Bugle Horn, and Moonlight will Come Again.

In October he was part of a quartet made up of Misses Annie Dunscomb and Annie Ewing, George Elston and Parker, that performed before a lecture of the Supreme Commander of the Knights of the Macabees at the Methodist Church.

The State Republican reported in November of 1893 that the wedding of Frank Ingalls of Chicago and Nelle Foote of Jefferson City was performed at Parker's house.

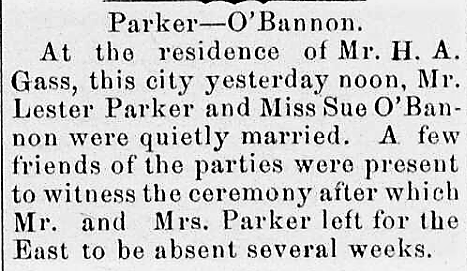

The Cole County Democrat carried this happy news in its May 10, 1894 edition:

Cole County Democrat May 10, 1894 p. 3

Mary Susan O'Bannon was 27. Parker was 34. She was the daughter of A. S. O'Bannon, who served as a state representative from Cass County for a couple of years during the Civil War. Their first child, Alice, was born the next May and their son, Lester Jr., was born three years later, in 1898. They lived at 124 West McCarty Street. But the second Mrs. Parker died in Chicago from peritonitis on September 3, 1899, leaving Lester with four-year old Alice and 17-month-old Lester Jr., to care for. She was buried in the family burial ground in Garden City, Missouri. The O'Bannon Homestead is now a National Historic Site.

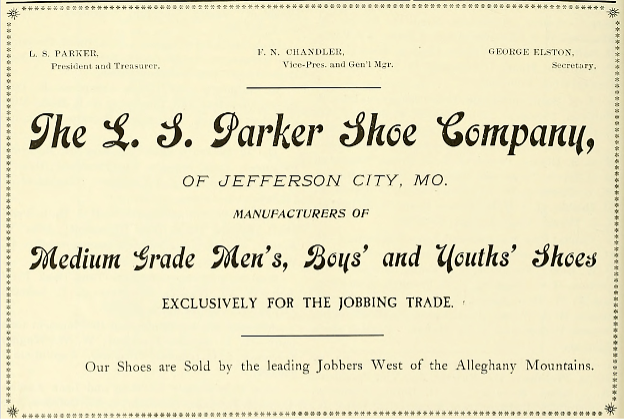

Henderson, "the oldest shoe company in Chicago" as it was then known, sold its operations early in 1902 to another company. By then, Parker had sold his interest in the company and formed a company of his own, L. S. Parker Boot and Shoe Co., with operations based inside the penitentiary. Longtime Jefferson City newspaperman Lawrence Luetkewitte recalled Parker became known as a "go getter who worked night and day…and had a passion for perfection at anything he undertook."

Shoe making---by Parker, August Priesmeyer (whose A. Priesmeyer Shoes building boasted, "Shoes That Wear"), and Giesecke Boot and Shoe Co.—was just one of the industries behind the walls of the penitentiary. The J. S. Sullivan Saddle Tree Company was one of the world's largest saddle tree manufacturers. The Strauss Harness and Collar Company used convict labor, as did the others, paying the state fifty cents a day for a man's work and forty cents a day for women's work. Thirty-eight of the fifty-four women prisoners stitched shoes.

Prison historians Mark Schreiber, Laura Moeller, and Laurie Stout write that "the penitentiary was the largest institution of its kind in the United States with just over 2000 inmates. It was also considered one of the most efficient: costing only 11¢ per day to house and feed each convict. The profit from convict labor was substantial."

Parker's company in 1900 employed 230 people with orders of 65,000 pairs of shoes. Not all of those working in those factories were inmates, however. Until a court ruling in 1901 that people younger than 21 could not work alongside convicts, boys as young as twelve sometimes put in eight-hour days six days a week.

(The Illustrated Sketchbook and Directory of Jefferson City and Cole County, 1900)

The National Prison Association said in 1905 that the Missouri Penitentiary was the only prison in the in the United States to more than offset its operational costs by the profits from prison labor. At that time, Parker's shoe and boot company was one of five shoe factories inside the walls, joined by the saddle tree factory, clothing and broom factories, and a binder twine factory that was considered one of the nation's best.

Local historian Gary Kremer records that Parker's factory paid the state of Missouri $52,148.07 for 73,289 days of convict labor.

Parker also was the President of the Economy Stay Company that made shoe stays and often used physically handicapped inmates to make thousands of the wooden pieces that were shipped nationwide. Schreiber recorded the company used 60,000 leather skins every year and needed even more when a special department started making "cowboy chaps."

A friend recalled that Parker made a special pair of shoes for a minister "who had the disconcerting habit of pacing during his sermons." Parker put a stop to the habit by making the minister a pair of shoes that squeaked as he walked.

Between his professional activities, his civic involvement, and his family responsibilities, Parker seemed never to be idle. Perhaps that is what motivated him to compose The Busy Man's Prayer, published in The Central Baptist magazine issue of December 12, 1907.

Parker sold his shoe company in 1913, four years before the prison industrial system was abandoned. But his experience was important to new Governor Frederick D. Gardner, who appointed him as the first superintendent of penitentiary industries, a job considered so important that it paid as much as the governor was paid, $5,000 a year.

In his new job, Parker was responsible for the operations of all of the now prison-run factories. During his term, a new law was passed authorizing salaries of the 1,500-plus inmates working in the factories of five percent of what they would have earned for private factory operators. The penitentiary reported in October, 1919 that its industries had a profit of $61,000. Parker decided that was a good time to retire again.

He spent his remaining years as a First Citizen of the state capital.

Parker might have "retired" from the shoe and boot business, but he was far from ready for the rocking chair. He had established himself as a leading citizen within a few years after arriving and in October, 1903, succeeded former Governor Lon Stephens as President of Central Trust Bank when Stephens moved to St. Louis. He served as bank president until January, 1905, when former Secretary of State Sam B. Cook was named president.

Although he was not one of the original organizers of the Capital City Telephone Company in 1900, he became its President and might have secured its survival against two competitors by buying back all minority shares in the company. By 1923, the company employed two dozen people with a combined payroll of $27,623.88 and "reached the outside world" with the long-distance service of both the Bell and Kinloch Companies.

He was known as a sportsman, an ice skater who was the first person in Jefferson City to perform figure skating, and an excellent golfer. He was known as a "Camel sniffer" by members of the Rotary Club, which he helped found in 1918, a person who did not smoke but after someone else lit up, would reach for the cigarette and pass it under his nose to smell the aroma.

He had lead mining interests in the Joplin area and raised cotton in the Missouri bootheel. At some point, and the record is not clear, he went to Paris to study art at the Academy Colarossi. In his retirement years he was widely-respected for his watercolors and oils, many of which focused on the Capitol and on scenes from his travels abroad. He gave 100 pieces of his art collection to the First Baptist Church, in which he was a long-time lay leader as a choir member, trustee, superintendent and teacher of the Sunday School. He also served on the Baptist State Missions Board.

The Jefferson City Tribune noted later, "In the progress of Jefferson City, Mr. Parker has been an important factor. When the first building and loan association was organized, he found time from his large business to help lay the foundation for a movement which has made it possible for Jefferson City to boast of more self-owned homes than any other town its size in the state."

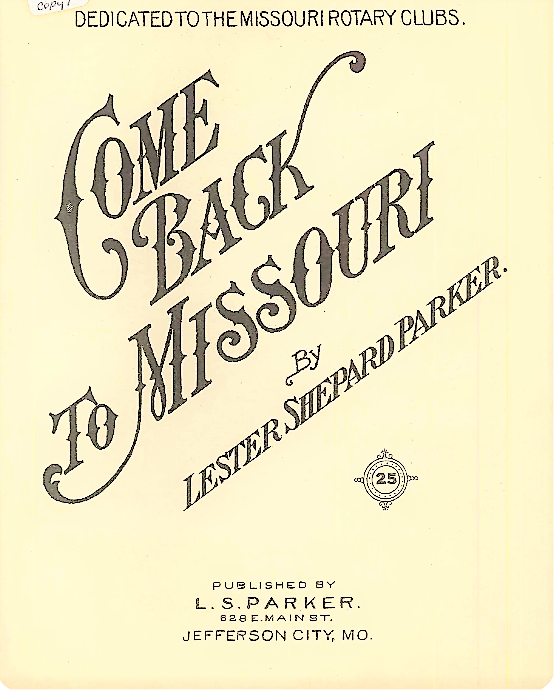

Among other talents, Parker was a composer. He wrote a song, "Come Back My Honey, to Missouri," that was one of many compositions at a time when the Governor Hadley was hoping someone would write a state song. Missouri did not have a state song until the late 1940s when the Missouri Waltz, a song that has almost nothing to do with Missouri, was approved by the Missouri General Assembly.

Some of his other songs are examples of a time when open racism was part of life for both whites and blacks: Rag Time Rastus and The Pickaninny's Lullaby, as well as The Whistler and People Will Talk, his most popular song. The Book of Missourians: The Achievements and Personnel of Living Men and Women of Missouri in the Opening Decade of the Twentieth Century, published in 1906, commented:

"Rag Time Rastus, the Whistler" is his most novel production and has met with hearty approval by the public and the press. It is decidedly unique in the line of song-writing and has a whistling chorus. It describes the predicament "Rastus," a Rag Time negro, and is humorous in the extreme. "The Pickaninny's Lullaby" is considered by many his choice melody, having in its makeup a definite purpose and being a true and practical description of darkey life. The coarse element found in most darkey songs is eliminated, and the ludicrous common to darkey character is pictured in a pleasing and vivid manner.

But to many, and his most popular song and certainly the most unquestionable hit, full of spice and music, is "People Will Talk," a most happy mixture of fact and wit. The music and chorus are by Mr. Parker, the words being adopted. The following are two of the stanzas.

If threadbare your dress, or old fashioned your hat,

someone surely will take notice of that,

And hint rather strongly that you can't pay your way,

But don't get excited whatever they say, for people will talk.

CHORUS:

For the people, all the people will watch you with eyes like a hawk,

Never sleeping,

Ever keeping

Their tongues busy wagging and talk, talk, talk.

If you dress in the fashion, don't think to escape,

For they criticize, then, in a different shape;

You're ahead of your means, or your tailor's unpaid;

But mind your own business there's naught to be made,

For people will talk.

CHORUS:

People will talk.

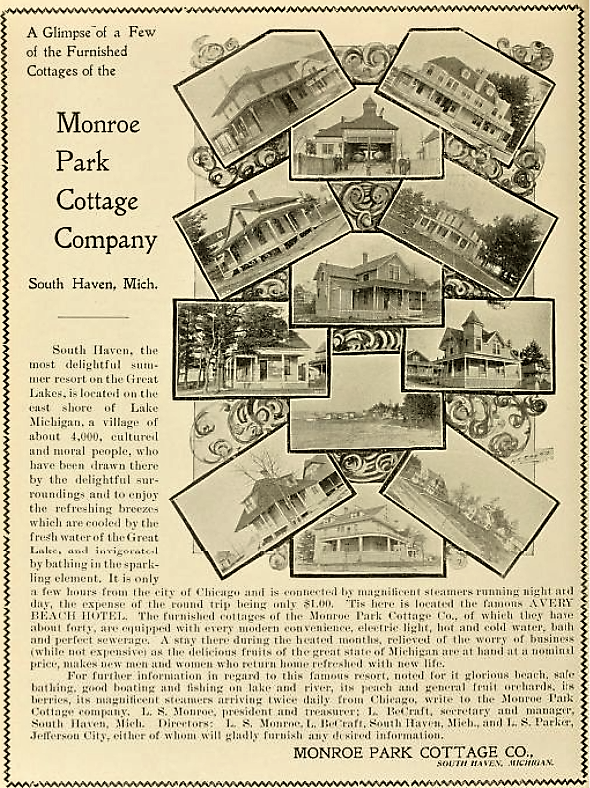

He was one of the original promoters of a summer resort on Lake Michigan in South Haven, Michigan. The Monroe Park Cottage Company owned several furnished cottages that were rented during the summer. The area became known as "The Catskills of the Midwest" and in 1900, steamships brought 160,000 visitors across Lake Michigan from Chicago.

Lester Parker married for a third time, to Missouri Gordon, in 1901. She went by her nickname "Zue." Their only child, Rachel, was born in 1908, five years after they built their home at the corner of Lafayette and East Main Streets.

Parker and future Jefferson City Mayor C. W. Thomas went into the real estate business together in 1905, buying property known as Cottage Place Park in the block west of Lafayette Street between McCarty and Miller Streets, then the outskirts of the city. Kremer recalls the area was the home of the city baseball field (or as it was often called in those days "base ball.") The area was for a few years the site of the City Horse Show and then the State Horse Show---which later moved to Sedalia when the State Fair was held there. Parker and Thomas bought the area for $8,000. They planned to meet the high housing demand in Jefferson City by subdividing the area into residential lots.

The three Parkers undoubtedly were among the hundreds of spectators who flocked to the Missouri Capitol on Sunday night, February 5, 1911---to watch it burn.

The Capitol, the central part of which was built in 1840, had taken a lightning strike to the dome and by the time the fire was discovered and the volunteer department could assemble its resources, the fire had too much of a head start. Its fate was sealed when the principal water main broke early the next morning.

Parker was among the leading citizens who organized the campaign to win passage of a bond issue in August to put up a new building that is today widely recognized for its architectural elegance and its artistic excellence.

Parker was part of the advisory committee to the Capitol Decoration Commission, appointed in 1917 to coordinate interior and exterior decoration of the new building. The commission's work was endangered when Cole County Senator William C. Irwin, a tall and intimidating figure, attacked the artwork being installed that told of Missouri's history.

Missouri Official Manual 1921-22

Irwin demanded the commissioners be replaced with "businessmen, not artists." He referred to the Oscar Berninghaus interpretation of the Revolutionary War battle of St. Louis as "an old fashioned piece of art." His objections forced legislation to continue commissioning art works to be set aside.

Parker considered the works "masterpieces" and his defense of them ultimately led to the establishment of a committee of Irwin, Parker, Jefferson City publisher Hugh Stephens, Governor Arthur Hyde and Lt. Governor Hiram Lloyd to work with the commission. The committee allowed Irwin to save face but giving him no authority to block installation of any art work or payments for it. Available records do not indicate the commission sought counsel from the commission in its selection of artists and topics.

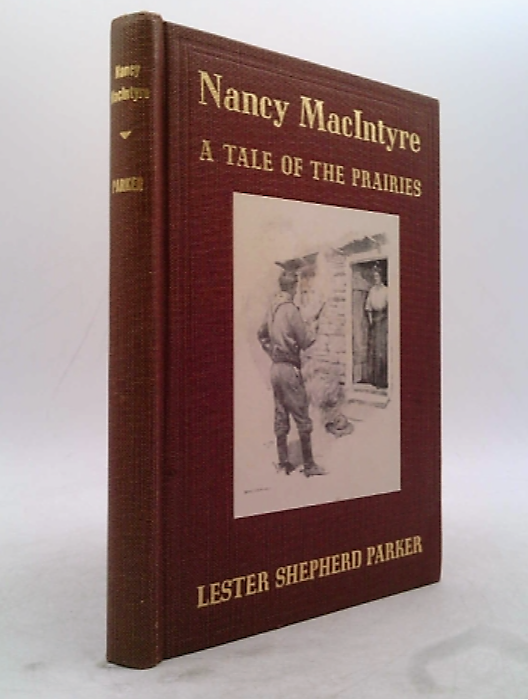

Parker was a year or so past his 50th birthday when he wrote a book that drew on his recollections of Kansas. The promotional literature referred to Nancy MacIntyre as "a simple love tale of the early days in Kansas, when the horse and the prairie schooner were still the only means of conveyance."

Nancy McIntyre, a Tale of the Prairies, was published in 1912 and it sold quickly. One source says it sold 36,000 copies during his lifetime. It was dedicated to "My Wee Daughter, Rachel Ellen Parker." The book went through several printings. He wrote in a rather enigmatic preface to the third edition, "It was not the prudence of man's mellow age nor the wisdom of woman's intuition, but the rashness of an author that prompted the first edition of "Nancy MacIntyre…The reader has somehow fathomed that this little heart to heart story---has guessed the truth---"Nancy" and "Billy" are not wholly creatures of the imagination. In her youth, not so very long ago, it was said of "Nancy" that

"Nature was so lavish of her store

That she bestowed until she had no more."

The 107-page book-length poem that sold for a dollar constituted the love story between a cowboy and the rancher's daughter. It begins with Billy's story:

No use talking, it's perplexing,

Everything don't look the same;

Never had these curious feelin's

Till those MacIntyres came.

Quit my plowing long 'fore dinner,

Didn't hitch my team again;

Spent the day with these new neighbors,

Getting 'quainted with the men.

Talk about the prairie roses!

Purtiest flow'rs in all the world,

But they look like weeds for beauty

When I think of that new girl.

Strange, she seems so kind of friendly

When I'm awkward, every way,

And my tongue gets hitched and hobbled,

Everything I try to say!

2

There's one person, that Jim Johnson,

That there man I can't abide;

He's been milling around near Nancy,--

Durn his dirty, yaller hide!

Never really liked that Johnson;

Now, each time I hear his name,

Feel this state's too thickly settled,--

That is, since that new girl came.

If this making love to women

Went like breaking in a horse,

I might stand some show of winning,

'Cause I've learned that game, of course;

But this moonshine folks call 'courting,'

I ain't never played that part;

I can't keep from talking foolish

When I'm thinking with my heart.

The book begins with "Billy's Story," then moves on to "Nancy's Story" before concluding with a happy ending that brings the couple together after a series of misfortunes and adventures.

The Parkers were central figures in the social life of Jefferson City, a small town of 9,664 people in 1900 that grew to only 14,490 in 1920. The newspapers still followed the social whirl of the city with short notes in several columns:

Jefferson City Tribune Feb. 7, 1909: Big Bridge party at E. J. Miller home. Mrs. Parker scored second highest score. Another column noted Mrs. Parker's sister, Miss Kate Gordon, gave a "chocolate."

JCT April 4 1909 reported on a dinner at Parker's and another column reported they had been cast members in a play.

JC Daily Tribune April 25, 1909—Zue plays the Station Matron. He's "Mr. Hayseed." The play is at the Jefferson Theatre on the 30th.

JC Weekly Tribune July 8, 1909: Parkers head to their summer home in South Haven, Michigan. The newspaper reported their return on September 25.

JCWT September 30, 1909: It's now Grandpa Lester. Daughter Grace Williams of Seattle had a daughter.

JCDT October 30, 1909: Mrs. Parker to entertain members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy at her house this afternoon.

JC Daily Capital News February 2, 1916: Art Club heard from Lester about prison industries' reforms. He is described as "always a pleasant speaker."

JCDCN September 1, 1918: "Our Sunday School Sermonette" written by Lester on David and Goliath (likens David to USA and Goliath to "German Militarism.")

JCDT November 21, 1918: Meeting at Parker home of The Equal Suffrage League

JCDT December 6, 1918: Zue is Secretary of City Canteen Committee that meets trains going through town carrying soldiers to serve them "light refreshments and a word of appreciation."

JCDCN June 8, 1920: Art Club meets. Lester "gave one of his splendid talks upon 'Birds'."

JCDCN February 2, 1921: Lester stars in play presented by the Daughters of the American Revolution, "The womanless wedding." Brings down the house playing "a negro nanny."

JCDCN, March 1, 1921: Lester refuses to run for mayor.

JCDN April 3, 1921: But Mrs. Parker, a former teacher, was nominated by Democrats to run for the School Board. An account of her victory was published three days later. She was the second woman to serve on the Jefferson City Board of Education.

JCDT July 27, 1921 reports members of the Jefferson City golf team were competing in the third round of InterCity Golf Tournament. Sedalia was first. Jefferson City was second, Columbia third, and Fulton fourth. Lester was one of ten members of the local team.

JCDCN October 9, 1921: "Lester Parker…who lived near O'Leary barn sends true facts to mayor of Chicago. Claims his home was the first house consumed by the fire…Mr. Parker made his first money selling wisps of hair from the cow that kicked over the lamp."

JCDCN December 18, 1921: Fireless cooker fire causes $75 damage to Parker home. Hole burned in the floor and a wall was damaged.

JCDCN December 22, 1921:

The Democrat-Tribune had a follow-up report on January 5, 1922.

JCDCN February 23, 1924: Painting of the Capitol rotunda by Lester is on display in the window of a downtown store. He explained his painting "carries out Hambidge's system of dynamic symmetry and will be known as "Symmetry's Appeal." (Jay Hambridge was a Canadian-born American artist whose compositional rules were adopted by several prominent artists in both countries early in the Twentieth Century.) The painting was done at the suggestion of the Capitol Commission, the body overseeing construction of the building. The article concludes, "The picture is attracting considerable attention and is regarded as a work of art by authorities."

JCDCN April 23, 1924: St. Louis Symphony performs afternoon and evening concerts at the Jefferson Theatre, sponsored by the Morning Music Club. Parker delivers a "brief but eloquent and touching memorial" for Mrs. W. A. (Louise) Dallmeyer, longtime leader of the club. "No one has resided here whose passing will project more of an enduring influence for the social betterment and artistic advancement our city than this sweet character," he said. The article contained his full eulogy

JCDCN July 16, 1924: The Baptist Missionary Society has an all-day meeting at the Parker house, hosted by Zue. The group will adjourn so members can go to the Chautauqua. The Chautauqua was one of two men to deliver "brief memorial addresses" for Rudolph Dallmeyer, "premier Jefferson City merchant." Dallmeyer, whose wife had died in April, was killed in an automobile accident on July 4 when his car, driven by his "colored chauffer, Pearl Nichols began a "friendly race" with another motorist in a Nash touring car. Dallmeyer told Nichols to pass the other car and in the process Dallmeyer's car sideswiped the Nash and "turned turtle" in the ditch.

JCDCN August 15, 1924: Lester Parker put in charge of the Capital Dedication pageant and program.

JCDCN September 14, 1924: The cornerstone for the new Baptist Church at Capitol Avenue and Monroe Street is laid. Lester Parker spoke about the church's history. His remarks were later placed in the cornerstone.

JCDCN December 17, 1924: The Parkers are planning a tour of Europe during which Lester will make sketches "illustrating incidents of the early Christian Religion." The illustrations are to be placed in the new Baptist Church.

JCDCN December 20, 1924: Fire reported in the garage building at the Parker house. It might have started from a hot stove in the room above the garage. Damage was estimated at $150 ($2400 in 2022 money)

JCDCN January 7, 1925: Lester Parker finishes his new painting, "Religion" which will be a mural decoration in the new Baptist Church. It is described as "an allegorical subject depicting the figure of a strong and sinewy man carving out of stone such religious characteristics as truth, faith, love, and charity."

JC Tribune May 12, 1925: Lester returned home last evening from his big trip, having stayed over in Washington, D. C. for a few days.

JCT May 18, 1925: In the "Society" column, Mrs. Parker told the Daughters of the American Revolution about life abroad. The newspapers contained several other stories about speeches by Lester recounting the trip.

JCT, May 23, 1925: Lengthy article (front page and a jump to page 3). Parker recounts stories of his trip to Europe and the Mediterranean. He brought back 41 color sketches of things he saw. He doubted that the "Zion Movement" would "turn over the Ancient Holy Land to the Jews" is not likely to succeed anytime soon because of "the strong religious prejudices of the population." He recounted how the group had arrived at Luxor after a five-day steamboat trip on the Upper Nile "on the day the mummy case was to have been removed from Tut Tank Ahmen's mummy, but Egypt forbade the process...Mr. Parker described his visit to the tomb when he beheld the gold encased case in the Sarcophagus with an exact likeness of the pharaoh and other articles."

He spent a month in Paris attending the Academie Coloressi and a week in London where he met with artist Frank Brangwyn, who was finishing "eight large decorations" for the Capitol (the painting in the first floor rotunda).

On the trip home aboard the Mauritania, he met movie Cowboy Tom Mix, who he described as "a real genuine fellow although he wore all his western regalia, probably at the request of his manager." Mix entertained the ship's company one night and remarked, "Folks, I'm just a horseman and when you take my horse away and put me in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, what can I do? Even on land, in London, when I rode one of those main streets, here came a flock of those two-story busses on the wrong side of the street. Gee! I was the only one obeying traffic laws."

The newspaper account says Parker enjoyed the trip but was glad to be home and had written a poem to commemorate the return. It was read at a Rotary Club meeting:

I have just toured the continents and sailed the seven seas.

I have gone the length of Egypt with her blooming flies and fleas.

Her history and monuments appall my sense of time.

And fill my mind with conjurings I now express in rhyme.

Her ancient tombs inspire me but I'll tell you what's the rub.

I want to see that grander site, my hometown country club. I went all through

the Holy Land

And sailed Lake Galilee.

I saw the sacred Jordan and its journey to the sea.

While a hundred solemn fancies came to me with every thought

That the ground beneath my feet was where the Master walked and taught,

All those adventures only come to those who roam,

And while that's me, just now I say, "I want to be back home"

I stayed in Villefranche, Rome, and Nice, of balmy clime,

And saw the Spaniard, Greek and Turk reach out for my last dime.

I heard cathedral organs of the most melodious tone,

And opera and cabaret in every Paris zone.

I'll tell you what is gripping me relentlessly and hard.

I want to hear the mocking bird that sings in my back yard.

I want to see my neighbors' dog and let him in the door,

And tell him that I've come back home to hear him bark once more.

I want to call my neighbors' cat and tell him something new.

I'm going to say, "I'm sorry, Tom, for throwing things at you."

There are some very happy things that come to those who roam.

But as for me, the best is this, "Just let me get back home."

He later displayed about forty paintings he had made while on the trip.

JCT May 22, 1925---"Shipboard Lecture by Parker is Now in Demand," said the headline. Parker's remarks about the trip weren't the only things people wanted to hear from him. On the trip back he delivered a lecture on the "Hen Pecked Husbands Protective League." He was asked to deliver it to the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. The invitation is "only one of a dozen" invitations he has received since his return.

A small newspaper article in the Tribune on July 6 told readers, "Mr. and Mrs. Lester Parker expect to go to Minnesota this week." Before they left, however, the new Baptist Church, erected on the site of the original church built in 1888, held its first service. Parker had been the chairman of the decorations committee and placed several of his paintings there.

He presented a history of the church during that celebration. The next day, the Parkers, with their daughter, Rachel, left for Rochester, Minnesota the next day for a three-week visit. But it was more than "a visit." The Daily Capital News told readers on the 18th that Parker had had successful surgery at the Mayo Brothers Clinic the day before and chances were favorable for a complete recovery. The reason for the operation was described as "a chronic ailment, which although not acute, necessitated the operation." A later newspaper account said he had suffered from stomach ulcers for some time.

In his absence, the Baptist Church organized a "victory week" to raise $40,000 for the church debt. The six-day campaign would feature special music at each evening meeting with special lyrics composed by Parker for six familiar hymns. The six hymns were published in a special folder for the celebration on Victory Sunday, July 26. One of the hymns was sung to the tune of "Revive Us Again."

We praise thee, O God, for thine answer to prayers,

For the promises fulfilled to the faithful who dare.

Instead of the familiar chorus:

Hallelujah! Thine the glory, hallelujah! Amen!

Hallelujah! Thine the glory, revive us again!

Parker wrote:

Hallelujah, make us give, Lord, Stay around with us yet

‘Till the last dime appears, Lord, to pay up your debt.

We pray thee, O God, give us strength to each heart

That none be delinquent in doing his part.

(CHORUS)

We thank thee, O God, for the power of thy word

For no task can appall us that pleases the Lord.

(CHORUS)

May the doors of thine house open wide to the throng

Of the city's unsaved who hear Zion's glad song.

(CHORUS)

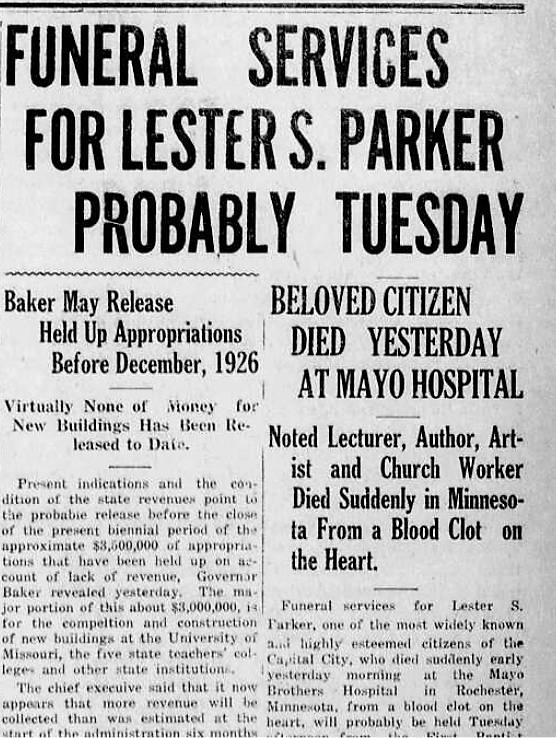

But on Victory Sunday morning, July 26, 1925, members of the church and citizens throughout Jefferson City opened the Daily Capital News to see a headline:

"The end yesterday morning came unexpectedly and at a time when Mr. Parker was apparently resting easy," said the article. Mayor Cecil W. Thomas said, "The loss is a great one to Jefferson City, far too great to be measured by words."

The newspaper commented, "No man in this city was more loved, admired, and trusted. Generous in sympathy, courageous in trial, devoted to his family and friends, true to his God, faithful in his stewardship, his place will be hard to fill, and the community will not look upon his like again…

"He had a fine sense of humor, a sound philosophy of life. He was a normal man, a Christian gentleman, and a useful citizen. He was admirable, democratic, big-hearted and unselfish."

The Daily Capital News said, "The death of Mr. Parker, which came like a thunderbolt from a clear sky, is universally regretted not only in Jefferson City but throughout all of Missouri."

Thousands of people attended the visitation at the Baptist Church on Wednesday, the 29th. Hugh Stephens, one of his closest friends, said in his eulogy, "He was a genius. Jefferson City was fortunate to have had him."

To him is due the credit for having rescued from defeat the movement to decorate the state capitol when that work had just started and was about to be given up. Single-handed he began a thorough study of the great purpose and aim of its decorations, and as a result we have in this city a building on which there has been expended for art nearly a million dollars, making it perhaps the greatest public building in that respect, within the bounds of the United States, except the Library of Congress. He was the first to deliver lectures on the subject here and elsewhere. He wrote a book describing the works of art, which book he published at his own expense. This community will never cease to draw dividends from the thousands of visitors who will come here as a result of the interest which he created.

A Parker portrait by Springfield artist Ralph Chesley Ott, was presented to the church to hang in the Lester Parker Memorial Room. The Parker paintings survived a church fire in the 1980s because they had been put in storage. One of his works remains on display at the church today but the fate of the full collection is unknown. His son, Lester Parker, Jr., donated two of his works to the Cole County Historical Society. A handful of his paintings are at the State Historical society in Columbia.

A year before his death, Parker had published a 72-page guidebook to the new building and to the artwork that had been installed by then.

Civic Clubs and the City council adopted resolutions in his memory. The Kiwanis Club said, "No man in Jefferson City ever filled a larger place in the life and affections of her people or did more for her civic welfare than he. He was a nobleman in the truest meaning of the word." The Lions Club praised "his upright citizenship, his faithful devotion to duty, his manly and courageous adherence to the right and his ever willingness to shape his daily conduct in accordance with the precepts of the Master who said, ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,' as well as his deep devotion to the duties which he owed to his family and to his God has exemplified in him the ideal citizen of this community."

The buildings Lester Parker used inside the penitentiary are long gone. The only building remaining in Jefferson City with a tangible connection to Lester S. Parker is this house at 624 East Capitol Avenue into which he and Zue moved in 1905.

Zue and Rachel continued to be socially prominent in Jefferson City. On May 27, 1931, Zue gave an informal luncheon at her home for a friend who was leaving the city in a few days. That evening, Rachel hosted eight members of the G.A.Ls contract bridge club. The next day they were off to Independence to visit Zue's sister.

Rachel would have been 23 on the day the newspaper was published. She and her mother are buried next to Lester in Riverview Cemetery.

The Daily Capital News on May 30 praised them for their "superior worth and valuable life and loveable characters" and continued, "Joyfully around the souls of many their spirits had entwined, all living truth and beauty, fruitage of heart and mind. None knew them but to love them, none named them but to praise. They were part of the best life in the Capital City of Missouri; the social, civic, and religious welfare of the community was richer and more serviceable and more beautiful because of the contribution they made to it."

The House at what was then 628 East Main Street was left to Alice and Lester Jr., the children from Lester's second marriage. The house changed hands twice a few months later and was turned into apartments.

Main Street, in front of the house, was given its present name after the 1911 fire destroyed the state's 1840 Capitol. Today West Capitol Avenue has replaced West Main for two blocks west of Jefferson Street, on the first of which is the State Transportation Department headquarters and the Lewis and Clark monument, and on second of which is the present capitol and its grounds that were built smack-dab on top of Main Street. Main Street extends west from the west end of the capitol through the Mill Bottom and into a residential area.

The Parker house and the building that had been their servants' quarters, now christened "Parker's Place" by new owners Jason Jett and Kevin Callaway, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.